Retinal Detachment & Tears

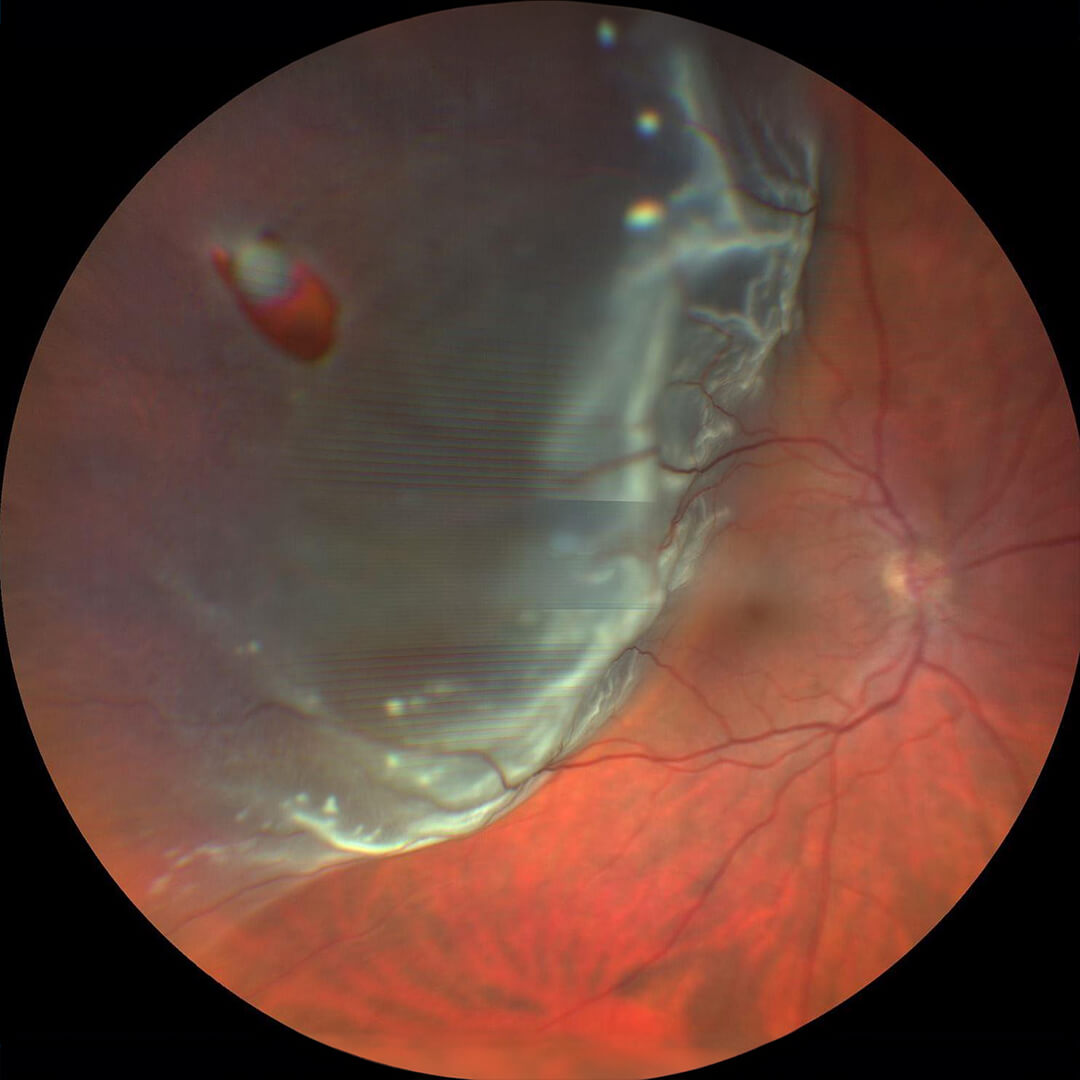

Fundus photograph showing retinal detachment

The retina is a thin layer that lines the inside back wall of the eye. When the retina detaches from the back wall of the eye, the retina does not function in that area and vision loss occurs, sometimes very quickly. Retinal detachment often starts in the side part of the retina where peripheral vision is located and then expands to involve more and more of the retina over time. The end result of untreated retinal detachment is usually blindness, but fortunately the retina can be reattached in the majority of cases with restoration of most of the vision. If the retina is repaired before the central vision is lost, the clarity of the vision often returns close to normal. If the central vision is involved, then there is often some residual central blurriness and distortion, but the peripheral vision is restored.

Causes of Retinal Detachment & Tears

In most cases, a retinal detachment starts with a posterior vitreous detachment. This occurs when the vitreous gel that fills the middle of the eye separates from the retina as it does in most people as they age. This causes only a few floaters most of the time, but sometimes it can grab the retina as it separates and tear it. If this happens, fluid goes through the hole in the retina and it detaches from the wall of the eye.

Retinal Detachment & Tear Surgery

If a tear is identified before the retina detaches, this can be fairly easily treated with a laser in the office, but a retinal detachment often requires more involved treatment.

There are three main treatments for retinal detachment. All treatments have in common that the holes in the retina are identified and closed. By doing so, the body pumps out the fluid under the retina and the retina stays reattached. Once the retina is reattached, laser and/or freezing treatment (cryotherapy) acts as a permanent glue to keep the hole closed, although these treatments take a couple of weeks to gain strength.

Vitrectomy

The most common treatment for retinal detachment is vitrectomy surgery. In this, the vitreous gel that is pulling on the retina and causing the tear is removed. The retina is reattached in the operating room, and the tear is treated with laser or freezing. The eye is left filled with either a gas or silicone oil bubble to push the retina in place and hold it there while it heals.

Although this surgery is relatively painless, it does require keeping the head in a certain position constantly for up to a week after surgery in order to maintain the gas/oil bubble in the appropriate position to hold the retina flat. Your surgeon will indicate the appropriate position after surgery. The gas will slowly absorb over weeks to months, but the silicone oil has to be removed with a second surgery later. The vision is often limited until the gas/oil is gone.

Scleral Buckle

An older treatment is a surgery called a scleral buckle. In this, a silicone piece is sewn to the wall of the eye in the area of the tears, leading to indentation of the wall of the eye and the closure of the hole from behind. A freezing treatment is done during the procedure to allow the tear to adhere to the wall of the eye. The silicone piece cannot be seen after surgery in most cases and remains permanently in place. Since no air or gas is used in the eye, positioning after surgery is generally not needed. A scleral buckle can be performed with or without a vitrectomy.

Pneumatic Retinopexy

In select cases, a smaller gas bubble can be placed in the eye in the office, avoiding a trip to the operating room. This is called pneumatic retinopexy. This is done when there is a single tear in the upper half of the retina. Since the injected bubble is relatively small, strict positioning with the head in a certain position day and night is required for several days in order to allow the bubble to cover the tear. This procedure carries fewer risks than vitrectomy or scleral buckling overall, but the success rate is slightly lower than for surgery. Surgery can always be done if this procedure does not work.